When I was at university completing my postgraduate diploma in broadcast journalism, my final project required a trip to London. Specifically the London Zoo.

I was researching the breeding of tigers in captivity by conservationist zoological societies. I wanted to understand the impact human development had on tigers, the depletion of their natural habitat and whether it would be possible to reintroduce young tigers born and raised in zoos, to the wild.

As I was based in Sheffield, I had to make all my arrangements before the journey from South Yorkshire to London. Being a student I was on my own dime, on a tight budget, and I could not afford to spend too many days in the expensive capital on accommodation, meals, transport and borrowed equipment from university.

I was excited to go, but conservative in my expectations about the experience. The British are generally media savvy. After all, this is the home of the BBC. Company spokespersons are trained in strategic communications and the average person on the street is always willing to offer an opinion about the latest political debate. So, while I was only a fledgling student, just stretching my journalist wings, people I interviewed or filmed were kind and patient despite my nervousness. I was humbled they gave me the light of day at the zoo with its management being so busy.

My pokey hotel room was a long walk from the zoo situated at one end of Regent’s Park. I felt an exhilaration as I moved through the park at the beginning of spring. Though I had travelled extensively by then, it was always during the hottest month of the year in India – May – and so I was often greeted by warm temperatures in Europe and North America (notwithstanding the occasional spring shower). After living in England through some cold, dry and mostly miserable months, this was the first time I really understood the meaning of four seasons and the slaking of a thirst for the sun and its bounty.

As I walked, I saw storks fly towards nests suspended like beehives from trees growing on an island in the middle of a large pond. A group of men in blue and red shirts played football in a far corner. A few new mummies pushed their sleeping infants at leisure. Dogs fetched balls and sticks, flowers poked out of green hiding. Everything held moist promise.

The park is massive, as is usual for most London parks. The zoo is spread across a few acres nearer the neighbourhood of Camden in the north west. I had to find my way mostly by park signage and asking people directions since it was before Google made things easy.

The bulk of the recording equipment I carried, along with the weather and the exercise made for a long, hot walk. By the time I arrived at the zoo and was ushered in to meet the Director of Conservation, I looked more like I needed temporary housing with the polar bears and an ice cream from the zoo’s cafe. After a cold soda and a few minutes we had a wonderful discussion about the zoo’s conservation efforts and the various levels of success amongst different species. The interview went well, she was articulate with an interesting voice, gave great soundbites, she had done this before and her confidence allowed me to relax a little.

After the interview the director asked if I’d like to speak to the main warden in charge of the tigers, ask him a bit about their habits, his thoughts on conservation etc. I had come to the zoo expecting only to speak to the director and then leave for a subsequent interview with a representative of the World Wildlife Fund. To get as objective a view as possible the script needed a balance of opinions. I did not envision the domino effect of the kindness of others and the networking factor. After all, there was nothing in it for them at the zoo – I was only a poor student, cobbling together a radio documentary for school.

I hurried along to the tiger enclosure where the warden was waiting for me, ahead of his rounds of feeding the tigers their lunch. My hands wrapped around the mike aimed towards him while he spoke, as we sat at at a bench nearby, the two tigers awake and ravenous, in full view, I felt I was in a dream. And then it got better. He asked if I wanted to go into the back of the enclosure to meet the adult male. He was kept separate from the females before feeding time and given a larger meal. My head almost exploded with joy.

—— continues in part 2 ——

I recently went on a date with a (grown) man who offered me lurid details about his colonoscopy. While having a roast beef dinner. Yes ladies and gentlemen, that is what you sometimes must endure when you start looking for companionship as a mature (wiser) single woman who doesn’t want to die alone. I’ll confess, I’ve had a strange run so far, ever since some lazy gene in me activated one day and went from a dull whisper to an all out banshee screeching: ‘get the fuck off your isolated ass and go meet men! It’s not as bad as you think.’ (Newsflash: it is though). After the first couple of surprisingly pleasant dates I almost believed the screaming subconscious monster. Then I went out with Matt[*].

Matt, who works as a military medic, had some fascinating stories about injuries sustained during desert warfare. Once we actually met each other in person he dropped the newsworthy bomb that he was married with two children. But it was cool though because his wife was agreeable that he get laid after the first drink on the first date with me. As flattering as that was, unfortunately for him, we didn’t want the same things, so I said goodbye and moved on to Jeremy.

Jeremy sounded lovely on Whatsapp. He sent me photos of his trips to Oman and Nigeria, as a geologist in the oil industry. Until we met and he also shared his opinion on how untrustworthy he found certain ethnicities, how he’d lived (and loved) in over 14.5 countries and was generally a panty creaming catch. He did send me a message full of hungover remorse the next day apologising for his vile racism. I messaged him back saying that ship had already sailed, on a slick of oil. But thanks for the follow up text.

Then there was Emilio, or so he called himself. He approached me at the marina track when I was red and sweaty from my run. Anyone who is interested in me post workout – or after I’ve just woken up – deserves the right to one date. However, Emilio deserted me before dessert was served. Said he was just popping to the washroom. From which he messaged informing me that he’d suddenly received news his mother had passed away. Huge coincidence as it was probably the exact second after it dawned on Emilio that I would not shuffle to a dark corner of a secluded section of the city’s public beach to indulge in acts of which I find myself incapable with men who sit so close to me the first time I can count their nostril hair and cheek freckles. Men who ask me, ‘do you think I’m hot? Because you’re hot.’ No sir, dead or undead mommy, that is a 128% turn-off.

There was Timo who showed up for our date a day late (a few angry texts into asking me my whereabouts I reminded him it was actually his fault. By then I was in a movie theatre stuffing my mouth with popcorn to Chris Hemsworth doing something. It was Chris Hemsworth so I don’t care what he was doing).

There was Armand who wanted the date to carry on until morning based on only me paying the whole way through, breakfast (he should be so lucky) included I’m guessing. And Nic (still don’t know if it’s short for anything) who told me he was part of a cult, which he could not name, whose ideology he would not share, but its influence was apparent on Nic. He appeared a bit zoned out when we met. Or he might’ve just been high. Way to make an impression Nic.

Some men have refused to take no for an answer. Early childhood rejection and the onset of middle age loneliness can do that to anyone. The concept of ‘letting him down gently’ becomes redundant after the ninth unanswered phone call. Sorry guy, you have now earned the Block Caller Award. I’m not renown for my patience anyway, so this prize is handed out with resounding frequency.

Some men have refused to take yes for an answer: yes you’re a fine specimen of humanity, yes I am captivated by you, yes I’d be very happy to take this further, yes yes yes yes yes! Make me say it. But no, they haven’t understood my value, they’ve lost the way to their minds or hearts or penises. Doesn’t matter, confused and/or closed off men aren’t attractive anyway. Imagine how lost they’d get on the path to your pleasure zones.

And finally, for the fantastical times it has worked out – for a moment or more – it’s worked out well. There’s a word for that. Chemistry. It’s a word I don’t throw around often because it doesn’t happen often (see examples above), but when it does it feels like an intact Jenga tower: a rare wonder we found so all our individual pieces fit perfectly to reveal something solid, graceful, sexy. And if that tower falls, he and I pushed it over together. Hard and fast. In sync. And no, I’m not going to kiss and tell. Magic stays that way if it’s kept secret.

[*] names have NOT been changed so others stay alert to these oddballs.

Dear Hugh,

Stop being awesome. If you insist on being awesome, be unmarried. It’s a very unsavoury combination: the fantasy of being Mrs. Jackman incessantly unrealised as you continue being tall, dark, handsome and generally mesmerising. So cool, so centred. Tell us mortals your secret.

Where do you get the motivation – as your co-star in one of the many X-Men movies (I forget which, I only remember you half-clothed in most of them) James McAvoy (no wilting daffodil in the attractiveness department either) has said, “to rise at 5 am to hit the gym was bad enough for us, but to get there and discover Hugh was already pumping iron an hour before was soul crushing”. Who ARE you if not some Australian Zeus with laugh lines to get lost in and a smile needing the smilee to hold on to their sunglasses? You do it quite freely as well. STOP in the name of all that is gorgeous! It’s very bad for my health – the tug of various parts of my body unable to actually snap back because you insist on defying being human.

I once saw a magazine photo of you riding the New York subway with your kids. A festering New York subway train whose plastic seats are smeared with all manner of lowly sheddings. That an earth-god deems to take some of the shittier modes of transport in the Big A is heartwrenching enough, that he teaches his kids to live like the rest of the grain, that’s plain evil. Again, let them eat cake. Let them travel by golden buses with your face (and pectorals) plastered all over the sides. Let them move around in Rolls Royce Phantoms with your torso as the emblem out on the hood.

Either that or date me so eventually I can be their step mother and then teach them a thing or two about entitlement. See, I’d be doing you and them a favour.

That brings us to Deborra. Your wife of some absurd plus years. The woman who seems to have captured your soul in a gilded love cage where you sit, quiet, calm and at complete peace with her ownership. True? You love slave you. You even said that on some radio interview once, you’re her love slave. Sigh.

The point of this enduring infatuation for you is that I imagine the following when I think of you (besides all manner of nudity):

That you believe in hard work and being open to life’s gifts.

That you’re over societal limitations on love and success and various other restrictive parameters.

That you’re 6 foot 2 and have built yourself to a (very) pleasurable body weight.

That your inner strength matches your outer strength and that I can imagine in moments of any conflict or weakness, falling into you would be met with support, kindness and generosity.

Am I projecting much? Prove yourself then! Come knocking at my door, I’m free most evenings save Mondays when I hit the gym for Zumba. But you can interrupt us, the instructor will understand.

Several uncomfortably lingering kisses,

Peri

ps: You may bring your co-worker and friend Liev (as in Schreiber) with you. I’m willing to share.

It’s on my cheek as I brush my hair. One long, full eyelash. It starts out thick and tapers to a slim curve. I lean closer into the mirror, lick the tip of my finger and remove it.

I wonder what this eyelash might bring me. I don’t doubt its wish fulfillment capabilities, I don’t question how one small shedding from my body will help in exchange of my heart’s some desire being granted. I only pause, chewing my lip, what do I want? What can this errant eyelash give me?

I desire nothing. And yet so much. I want my child to be safe and at peace where he is, continents apart from me. I want to believe in the goodness of a man unafraid of my intensity and candour, an equal romance. I desire to connect with the whole world through my creativity. I desire success in as much as being understood as an artist can yield success (poor Vincent van Gogh). I desire all my friends are visited by joy in the tiniest way from my presence in their lives, I desire my parents seldom get sick, my pets die peaceful deaths, that I travel to many places and meet many crazy people. Super high expectations for one little eyelash, heavier than the mascara it bore.

I close my eyes and whisper to this lash in the bright bathroom, as if shutting out the noise of light will make the wish more concentrated, like a hushed auditorium before the orchestra breaks out Beethoven’s 5th.

Dear Dark One of collagen and hope, grant me the humility to be satisfied with what I already have. Help me to be thankful for a life brimming with people who I love and who love me, with activities I enjoy at my desert doorstep. Let me soak in the grace of each moment I am alive, being funny, being brave, being curious, being kind. Being present. That’s my real desire. Full of sentimental silliness, less constructive than when I started to formulate my list minutes before. I’ve surprised myself, I’m not as greedy as I thought I was.

A gentle puff and it’s gone. Down the drain, onto the cool tiled floor, perhaps back on my skin, making me reabsorb its meaning… who knows. Only the manifestation it carries is of relevance. The prayer imbued in it. The power of an eyelash.

I went to an all-girls school. We had little awareness of the budding magic of our young bodies, we did not have boyfriends, a party was a sleepover with amateur manicures and gossip. We did not have any internet, our reputations were built on the quality of our grades and who was in detention more than once that week (me, often). So though my teenage years were crammed with tumultuous loneliness, they slink off in shy deference to my son’s upheaval filled ones. What Sindri has experienced in the last few years is nothing short of Icelandic weather – storm clouds at the ready to hail down and four minutes later the Artic sun smirks through, changeable.

He was born in London. He’s been to five schools so far: two in Reykjavik, one in Mumbai, one in Dubai, the latest in NYC. He’s collected several friends along the way. He has understood something of the world in a framework others his age in one place would not. He’s the product of mixed ethnic heritage and two people who could not be more unalike. Now Sindri straddles the bridge between his own identity and the world as he has experienced it – diverse, packed with human emotion. He has seen first hand his mother – at times reluctantly – adjusting to live in cultures in stark contrast to her own context. He has experienced his father’s metamorphosis from a very grounded personality to one of more fluidity. He has spoken English, Icelandic, French from an early age, gathering Japanese and smatterings of Arabic and German along the way. He plays Chopin and Rachmaninov but listens to Drake and Stormzy. One minute he wants to be a zoologist, the next study political science, the next a journalist. Too much for such young shoulders, perhaps not enough for a boy of his intelligence, curiosity and grit.

Yet, who is this person growing up and away from me? A runaway balloon the receding string of which I grasp at uselessly? How did he get to this place so damn fast? Why did he not come with a warning label “Caution: Secretive when coaxed. Learn to let go with age”? Why do I feel this incessant need to know what he’s going through, to protect him? Is the animalistic mother in me unwilling to accept I am no longer responsible for his journey?

It’s hard to walk the other way in the fork in Life’s road, watching him become a mirage – close enough to feel I know him – this is my son! – yet the more I reach out, the greater the illusion he’s just a few miles gone. And the prayer, dear god, keep him safe! Let him make sensible choices! I am not around to tell him off, I can’t rescue him. Help him learn to rescue himself.

In Finding Nemo, Nemo’s father Marlin and his friend Dory are inside a whale’s mouth when Marlin cries, “I promised him I’d never let anything happen to him…” Dory, the film’s Quixote quotes, “Hmm, that’s a funny thing to promise. You can’t never let anything happen to him. Then nothing would ever happen to him. Not much fun for little Harpo.” (She keeps forgetting Nemo’s name). I have some Doryish friends who remind me it’s all going the way it’s supposed to… I need to focus on my career, my other relationships, my relationship with my spirit. After fourteen years of having a strong sense of one role, I need to switch and learn new skills…

Like how to think of myself first.

Like how when I cook, I only have to consider my own diet.

Like how while choosing a movie to watch, its age rating is no longer relevant.

Like how when I look at the empty bed with a Sindri shaped crater in its mattress, to smooth its sheets, rearrange a pillow and send him a silent plea – be careful, be kind, be calm.

How I don’t need to be home from work every evening to fix him a snack. How I can be where I want, when I want, with whom I want without the umbrella of Sindri’s care to contain those movements. How in a place separated by many seas, Sindri is waking up to his day as I get into bed ending mine, our prayers for each other different in askance, the same in tone – please let the other always know I care. How love is a word needing no other presence except in the heart of those who feel it for each other.

And so Life goes on.

Bedtime – for Sindri at two years old

I say “once upon a time” as I put you to sleep and hope you will dream

of mako sharks and kings with wings

and the elephant god

While I lie eyes wide open near you

recounting each instant each hope of mine

framed around your breath

I tell you of Zeus and Hera, the love for three oranges and a dancing cow

so you cannot see me

clutching at my nervous heart

The daggers are drawn, the duel begins

but before it ends you drift off

padded by white sleep

I am still in my story I can’t complete it

I don’t know the end for I keep changing the beginning

As I stay awake wondering about it near you

31 January 2006, Reykjavik

Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.

You are the bows from which your children

As living arrows are sent forth.

-Khalil Gibran-

When he was two I’d often ask my son how old he was, to which he’d respond, “I’m twenty-six!” with all ten fingers raised. I’m not sure from where this came but it was endearing and though I corrected him, “sweetie, you’re two! Say two?” – he stuck to his double digits.

One morning as we were cuddling in bed I squeezed him and said, “I love you”, to which he answered, “I love you”. I told him he could say, “I love you too”. The immediate come back was, “Mama, I love you twenty-six”.

Sindri Desai Gíslason is now an adolescent. Fifteen years old, on the threshold of being a man. He’s (almost) the height of an NBA player and if he listens to this memory one more time, the eye roll will be accompanied by, “Moooom, stooooop, this is so lame, I’ve heard it before, like, thousands of times”. He will not understand that in the retelling of it, he becomes my small child once more, something so pure and so fleeting, that reliving the memory is the only way for me to cope with him hurtling toward adulthood. And so far away from me while he’s doing it.

I was a young-ish mother, delighted to have this perfect human being in my life. The realization that I was capable of such deep love for someone caught me off-guard. This wasn’t what poets wrote about, around what movies spun glistening webs. Up to that point, romantic love was where everything lay – all glorious celebratory emotion. And yet. This overwhelming oxytocin charged sensation coursing through my body was my unconditional love for my child. Genetic biologists refer to this as a need to protect progeny in order to ensure the procreative process has not been futile, and they will go on to inherit the earth – that is, it’s all about survival, the passing on of our (strong) genes. With our intelligence, we have emotionalized this basic instinct, we’ve made it about love.

This kind of love is huge. It’s full of highs and lows – the win of the medal in the sack race, the fall from grace when he wants to be friends with the cute little girl blonde but she only has eyes for the cute little boy blonde, the constant Band-aid applications, the bad dreams, the delight of a Lego finished well under time, the ache of an average grade despite his hard work.

How does a mother cope with the loss of these small gifts? How does a mother move on from motherhood like this – the kind of role that defined her actions, her thoughts, her raison d’etre? Where does she find salvation once the die has been cast out into a relentless hard knock world, where the phone calls needing her peter down, where the worry is locked unmentioned, where unprotected and uncontrolled, the young man she has loved since he was a baby, now goes forth to conquer his realm, armed with a sense of youthful bravado and little else.

He reached all his targets a little too early – when he started walking was when he started running. He was in the ninetieth plus percentile in his growth chart. He learnt how to read sooner, he matured quicker. He’d run to defend his friends against bullies, and cry because when they hurt, he hurt equally. His sensitivity and kindness were boundless. His kindergarten teacher told us they had trouble putting him down for afternoon naps, he required a steady stream of stimulation. And when he hit his teens, he was the first amongst his peers to sport a fuzzy growth on his upper lip. He also left me at fourteen years of age, to live with his father (we divorced when Sindri was five) three continents and nine time zones away.

It was a decision we made collectively as a blended family – the opportunity to study in New York at a prestigious school outweighed the benefits of the education he was receiving in Dubai. He was also at an age where he needed his father as a male role model and needed guidance on how to be a man. I realized as he moved through his early teens with me that I was unable to be both mother and father to him. And his father, was welcoming and excited to have him be with the new family (of a wife and baby).

So here I am now… eighteen months into this painful umbilical separation wondering who I am if I can no longer mother him actively. When he was with me in Dubai, we rescued a dog from the kennel (who was returned because the building threw a no-canine contract in our face) and then two very loving cats. An odd family for sure, a single mother, a single child, a single quiet cat and a single sanity-questioning one. It was ok, it felt like something with truth and meaning. But of course, with a whole future ahead of him, this was not enough for Sindri. And – then, was it enough for me?

After all, I’d started writing young, my talents were put to use by my birth country’s leading national newspaper. At seventeen I had a byline in the Times of India, I was earning an income, fraternizing with important and beautiful people. I continued my journalism career in London, turning from print to broadcasting, reporting for the BBC World Service on everything from dwindling wild tiger populations to the effects of mixed marriage on religiosity. It was a heady time, I felt liberated with my self power. And yet, I remember that moment I told a colleague that if I didn’t get pregnant by thirty (I was twenty-six), I’d adopt a child. I was clear I wanted to nurture and love a small human being despite the absence of any large romantic ones at the time.

When Sindri’s father and I met and married, the greatest gift we gave each other was this wonder – wiggling around, needy, yelling to be held, to be cleaned, to be fed, totally helpless. And now, fifteen years later, he’s pushing back, totally owning his independence, totally not needing anyone for anything. A rebel, no causes. A tall cocktail of contradictions, logic and reason, emotionality and anger, completely self absorbed in teenage rage, hormones, unconnected neural pathways which lead to behaviours I don’t understand. Not even when I recall my own angst at his age.

To be continued…

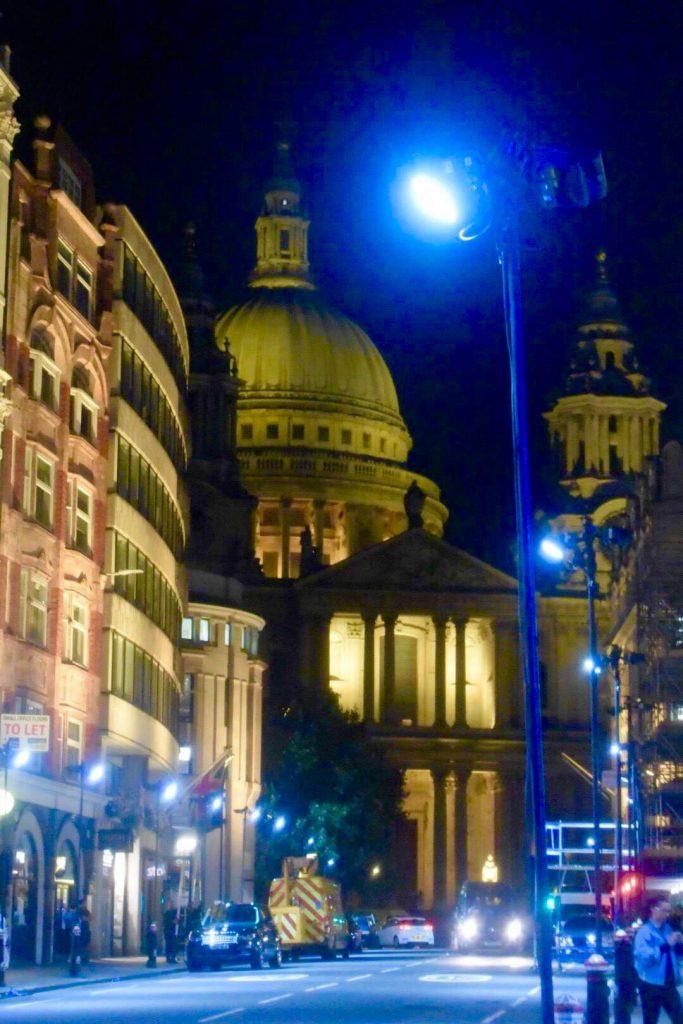

St Paul’s Cathedral

At times I lie here

under quilted half sleep

I think of your cobbled madness

tucked into alleyways of rogue tourists

At times

the lull of a metro worm here

reminds me of sooted nostrils there

Of gaps to mind

Of the blackness of my heart rolling up

an escalator rail to emerge in a volcano

of never expected English evanescence

The damp morning quiet

Birdsong in birth

The memory of so much

too hard to contain in one heart

Of yearning and learning

of love

of role-playing and pre-something

and post-everything

Oh old crone with your crystal glass in

expansive greens

And the riot of religion, language and flower

Spires wedged deep in ever cloudy skies

The smell of you seeping from my pores each day

Each day I am reminded of you

Each day away from you

the longing to keep being half-asleep

increases

Dubai, 20th Sep 2018

For my grandmother on her birthday

(after Alex’s St. Paul’s at night)

The amygdala is the most used part of my brain when driving in Dubai.

Yesterday I visited a friend who lives in a flat in a gridlock of buildings along Dubai’s overdeveloped seafront. It’s a 7.5 minute walk from my home, but I opted to take my car. Foolishly.

Driving into and out of this labyrinth of plazified skyscrapers is an exercise in patience as one wrong turn, one missed right, can land you at the outskirts of town, surrounded by sand, where no Google Maps satellite can help you. You may wander about in your dinky VW Polo (which is probably the worst buy for the city roads teeming with Range Rovers and Hummers – power – and Maseratis and Porsches – sexy power) looking for signs of life, while moving toward the distant watery blur of high rise concrete as your only hope of survival.

Driving or walking in Dubai has to be one of the best tests of tolerance in the world. You start out with good intentions and leave enough time to make it to your destination. Everything is only 23 minutes away, how mbad can it be? It can be so bad you will want to poke your bellybutton a couple of hundred counts with a kebab skewer because that would be less painful.

Dubai in all her golden glory is annoyed with your self-assurance, scoffs at your temerity to believe you’d get ANYWHERE in 23 minutes – even the corner grocery store – and spites you by spitting you out into the undigested bowels of her industrial district, making you desolate at 40 degrees – and at this time you are inside your vehicle with the air-conditioner on – until the semblance of a sign of a road you remotely recognise rears its familiar self. Ah, you think, I’m ok, I’m not going to die in the desert, dehydrated from days of being lost in Al Quoz (the city’s warehouse repository). However, you aren’t out of the dunes yet so you control your relief, ask Siri what’s going on only to be told “I’m sorry can you repeat the question” repeatedly until you’re back at the baby powder processing plant you passed just under an hour ago.

Megapolis madness or highways of hopelessness?

There are no statistics for people wasting 85 minutes in the desert on their way to a location 7 minutes away, but with the very unscientific support of anecdotes I can guarantee this happens to about 1 in every 2 persons. I have friends and colleagues who mention they’ll be there soon only to miss the meeting and resurface in perhaps the sands of Saudi Arabia. Sending a location pin doesn’t help because it isn’t about the accuracy of the location as much as finding the actual roads that lead to it.

It must have something to do with the diverse workforce. Filipinos, Russians, Indians, Sri Lankans, Afghanis, Koreans, Chinese, Ethiopians, Zambians, Englishmen, Irishmen, Icelanders (there are a few), Iraqis, Australians, Canadians, Costa Ricans, Chileans… the sheer volume of cultures residing within one context in this Middle Eastern oasis needs a single binding force, some regulations, some parameters to govern them all… Something which acts as an adhesive to the collective consciousness in order for all to respect the other’s way of life while being at liberty to keep their own.

As I walked along the city’s marina last night, lined as it is with trillion dirham yachts, I saw many middle income families out for a stroll, clusters of young labourers on their evening off, laughing in good weather, a few fit couples out on a run together, the abaya-clad aunty with an adored niece. It was 9 pm. In other cities of the world this may constitute crime curfews, where such a mash of ethnicities and earning brackets begin to feel the heat on the street and retreat indoors to the safety of their home. Not so in Dubai (where the street heat is only literal). Perhaps because of the same reason the roads afford no respite from the relentless round-and-aroundness I experience when I don’t take the right exit.

Rules. Rules are the backbone of this society, brimming as it is with people from far flung parts of our planet. Rules here condense everyone together in one cohesive cloud, working jointly at protecting the city while keeping it cool in the shade. And boy are there some rules. Some clearly communicated, some unwritten. And while some aren’t taken as seriously, others are imposed with enough fervour to make a devout Catholic ashamed (actually very little doesn’t).

The metro has strict rules of conduct – no eating or drinking, no chewing gum. Zero tolerance for drunk driving (you need a license to buy alcohol which can only be given once you proffer a no-objection certificate from the closest male in your life – your husband, your father, your boss). Most petty thefts, peddling goods without the proper license etc. can land you in jail with a marked path to deportation. Any licentiousness toward women is a crime and punishable with varying degrees of severity. Heavy fines are imposed for wrongful and/or dangerous road behaviour (from the mild like illegal parking to the bank breaking crossing-a-tram-line). I was once sternly told off for walking through a pedestrian red light (I blame being too caught up in Stevie Wonder’s Sir Duke playing in my ears, I could feel it all over). I have also paid more than half my salary in speeding tickets.

The mirage of closeness. It looks 5 minutes away but will take 55 minutes to get to.

This mentality for strict order probably applies in the urban planning of city streets. Highways are built not to send you to hell whether you’re from Hungary or the Honduras. It doesn’t matter how you drove in your country, if it was on dirt tracks with no marked exits so you could escape just as suddenly as you appeared or you tore through traffic in a tough Toyota Tundra. In Dubai you will drive on roads built to ensure everyone is protected against you, you will take the last exit to nowhere and do 58 kilometers back on yourself, but you will stick to the rules damnit. In Dubai you will jog along the promenade of the pond next to which you live, but should you long to crossover to the other side you may need to factor in about 33,009 additional steps because your path will take you over the ramp of the bridge, lead you up 4.5 additional flights, across the walkway, down another 3.1 flights, onto a sandpit bordering as yet undeveloped property (which will be a high-rise in 22 months) from which you will go under the over, desolate and quiet, to finally emerge where you wanted to be and could have been within moments if you weren’t walking in Dubai.

Hello, this is where I came in. And if you’ve stuck with me so far, you’ll do fine driving near-miss Dubai.

I believe each person is equal

let’s not deceive ourselves by creating differences then say they existed before we were born

I believe the colour of human skin differs

but we all bleed red

We all shit and piss the same way

Cry and love and light up when praised

I believe animals heal humans more than the other way round

And we destroy our healers

Sages who accept

who are wrecked by the bullet of pride, greed, something inside which can’t be quelled with trophies

I believe god is in the buzz of a bee’s wings and the autumn leaf

falling graceful slow to Earth’s carpet

In a sleeping infant’s soft wheeze

And three green lights in a row on a morning I am late to something

Steam warm circles on winter glass, write your name, believe the memory of you will stay long after it’s dry and cold

I believe freedom is discriminatory and has no value without the support of its environment

I believe who you love, who you fuck, what you eat, what makes you cry is nobody’s business

The child you couldn’t, didn’t, needn’t, shouldn’t, mustn’t have had not had had not had had

I believe I am only mine and no weight of guilt can make me love myself less, can shame me, can tell me how I feel

I know what I feel

don’t explain

I believe in a universe of infinite connections, so supernaturally strung as to celebrate or destroy lifetimes of labour

Like ourobouros we reinvent, reconfigure, realign and gain momentum in the many kindnesses around us

I believe there is nothing better than this moment

I believe in this moment

Dubai, March 2017

I exult in the fact I can see everywhere with a flexible eye; the very notion of home is foreign to me, as the state of foreignness is the closest thing I know to home.

Pico Iyer

Living in Dubai, a city with one of the world’s most diverse populations due to its dependency on a large ex-pat workforce, I am often asked the ubiquitous question, “so, where are you from?”. It’s an impossible one word answer for me, as it must be for an increasing number of people, who like me, have lived half their life across a rapidly globalized planet.

To start from the very beginning – an Indian Hindu man marries a Parsi Zoroastrian woman. Their first born is me. A most inauspicious start to the idea of one person being only from one place with one religion. Mixedness begins in my marrow, it spreads outwards across the rest of my life like a vibrant watercolour.

The Indians themselves are a mixed lot through centuries of foreign invasions, from the Mongols to the Macedonians and every pillaging demagogue in-between. There is no such thing as one Indian alone, just as there is no one pure Parsi. Some Parsis harbour the illusion that their ancestors, who arrived from Iran on the shores of India several centuries ago, managed to keep their loins off limits to the local populace. A fallacy in itself due to the fact that Parsi landowners, given large portions of property by the British – had sex with their Indian servants. Their progeny were indoctrinated as Parsi through a patrilineal rule which allows the Parsi man to call his kid a Parsi. However, my Parsi mother was ex-communicated for marrying a Hindu, barred from entering the temple where she had been confirmed into the faith at puberty and her children (my brother and I) unrecognized as Parsi. Which is just as well, as the notion of the accidental refugee had already started before my birth.

Parsis are refugees. Those living in India believe they are Indian as much as those living in Canada believe they are Canadian. Freddie Mercury, a Parsi, was by that logic, a Zanzibarian. What does “coming from” a place where you have no history of rooting mean in your current context then? Are you really an African American if you’re Black in the States? Are you a British Bangladeshi if you’re Brown in the UK? Are you even Parsi, if your ancestors are Persian? Are you an Argentinian or Portuguese or Israeli if you have light skin, curly hair and don’t match a viewer’s idea of what an Indian ought to look like? If I was born in Shanghai, would I be Chinese? I have been asked for directions to places in Hebrew, Spanish, Turkish and Italian while walking through the streets of Reykjavik, Brussels, Istanbul and Milan respectively. One Beiruti shopkeeper was adamant I was really Lebanese and pulling a fast one on him when I told him I don’t understand Arabic.

Perhaps some people give away a stereotypical assessment to arrive at a judgment of where they’re from in its conventional questioning – for example, Satya Nadela is an Indian immigrant, Salma Hayek, a Latina of Mexican origin. Do they really “look” like anything specific? In the big jumble of global movements, where do they fit, what would they call themselves? What do I call myself?

A typical dialogue between me and a person I just met may go something like this:

Person I’ve just met asks, “so, where do you come from?”

Me, “how long do you have?”

Also me, “I was born in Mumbai.”

Also me, “I have lived here and there.”

Also me, “I come from refugee stock, and if you ask me again in a few years, I may be just as obtuse then.”

Mixed heritage isn’t the sole factor which disallows me to conform. Having lived in different countries on different continents with distinctly different cultures isn’t the only reason I find myself unconsciously disengaging from someone who wants to box me into one idea. How do I explain that some of my heart’s shattered smithereens are at present hovering in the London air? That an Icelandic passport makes me long to show off the phoenetic ruddiness of the “Rs” of its language? That having a son who is also mixed has me truly believe we will all be “Beige” 50 years hence… a mash of non-ethnicities, determined by multi-DNA, our children able to come together in a wave of love and understanding. Schools will teach “Being Beige” as a history subject, countries will declare “Beige History Month” in honour of all mixed race people.

True belonging isn’t based on the man-made concept of a nation-state. Real identity is not hemmed in with where you were born or what language your mother speaks or how you look. It’s the spirit which moves you to say “I really love New York, so I came back to say ‘hey’” when the immigration officer asks you the reason for your visit (it made him crack a smile). It’s the call of your soul to sway to the beat of that distant drum, far away from the band in which you were told you HAD to sing. Real identity is accepting that your bones are yours, you take them, along with your backpack to anywhere you want to go, because you carry everything that makes who you are within them.

© 2018 Peridesai.com. info@peridesai.com All Rights Reserved.